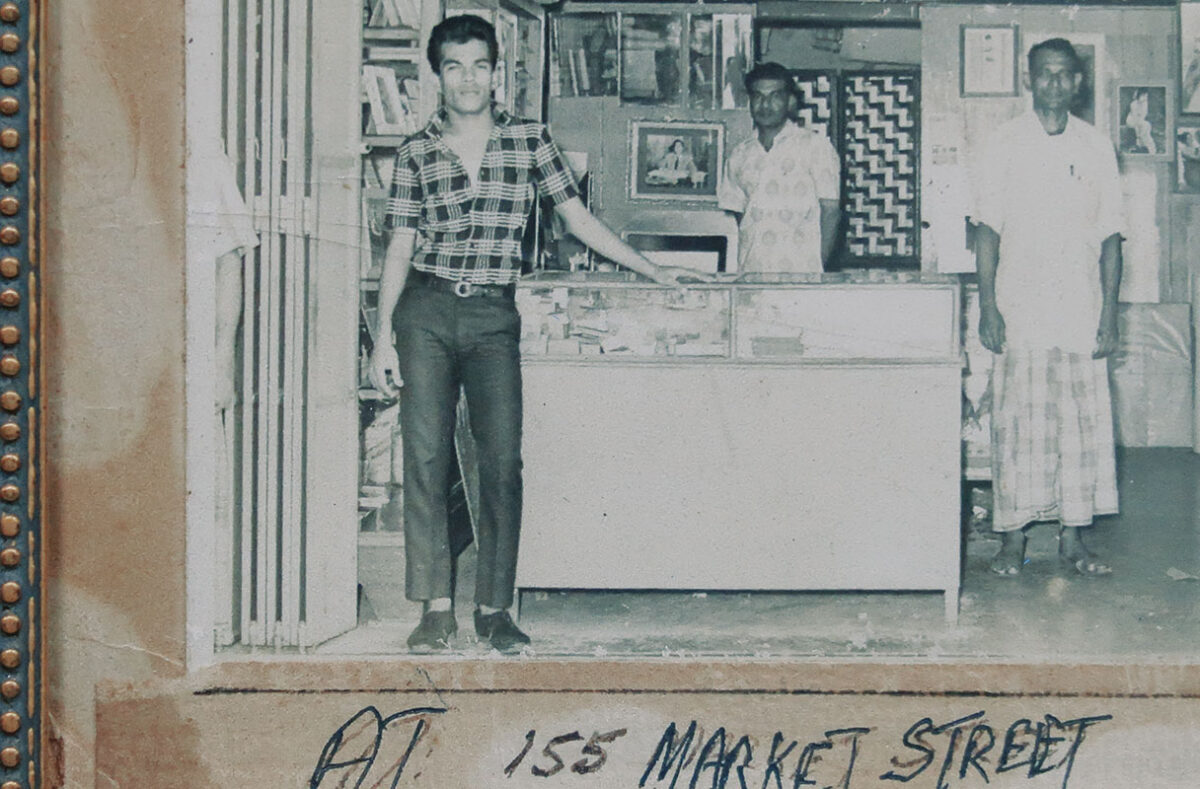

Project Framing Balikpapan (PFB) evolves from an encounter with a local frame maker in Singapore. I first met Maricar when he had just returned to Joo Chiat Road after a year-long hiatus, at a time when I was searching for someone to frame two artworks. These works had originally belonged to French visual artist Gilles Massot, who entrusted them to me when he left Singapore after forty years of living and working there.

Massot had been part of Singapore’s contemporary art scene since the early 1980s, contributing significantly to its development. Among the works I received was Journey of a Yellow Man No. 2, acquired by Massot in the 1990s directly from the late Singaporean artist Lee Wen. The other was an untitled photomontage that Massot himself created in Balikpapan, Indonesia, in 1992.

During the height of Covid-19 in Singapore, many small local businesses were forced to shut down, and Mr. Maricar’s frame-making workshop was among them. He suspended his practice for a year before resuming it, only to return to a transformed Joo Chiat Road, lined with new businesses and cafés that had rapidly sprung up. Against the backdrop of inflation and the pressures of a waning trade, Maricar has found it increasingly difficult to sustain his workshop in the post-pandemic economy.

For many years, his workshop had functioned as a meeting place for the local community. The traces of this role remain visible in the objects and personal belongings scattered outside on the pavement. One such presence is Ah Tat, a friend in his nineties, who ekes out a living on the street by repairing faulty convection warmers for neighbouring vendors.

These encounters reaffirm my interest in the street as one of our most fundamental public spaces, a site where localised social practices are made possible, yet increasingly obscured by the forces of gentrification.

Ah Tat (90s); Maricar’s friend, 2022

The workshop’s regular visitors largely come from the Malay community, many of whom once lived in the kampongs of the area before their eviction in the 1980s. This neighbourhood was among the earliest Malay settlements in Singapore and remains known to Malays across the wider archipelago, including Brunei and Indonesia. Some of Maricar’s friends even describe themselves as the “real locals,” positioning themselves as among the last indigenous residents of the area today.

In conversation with one of them, Jamal, I learned of his childhood memories of the communal riots between Malays and Chinese that once unfolded directly on the street outside Maricar’s workshop. While it is not my intention to historicise these encounters, such recollections nevertheless provide a layered context within which an engaged art project might unfold.

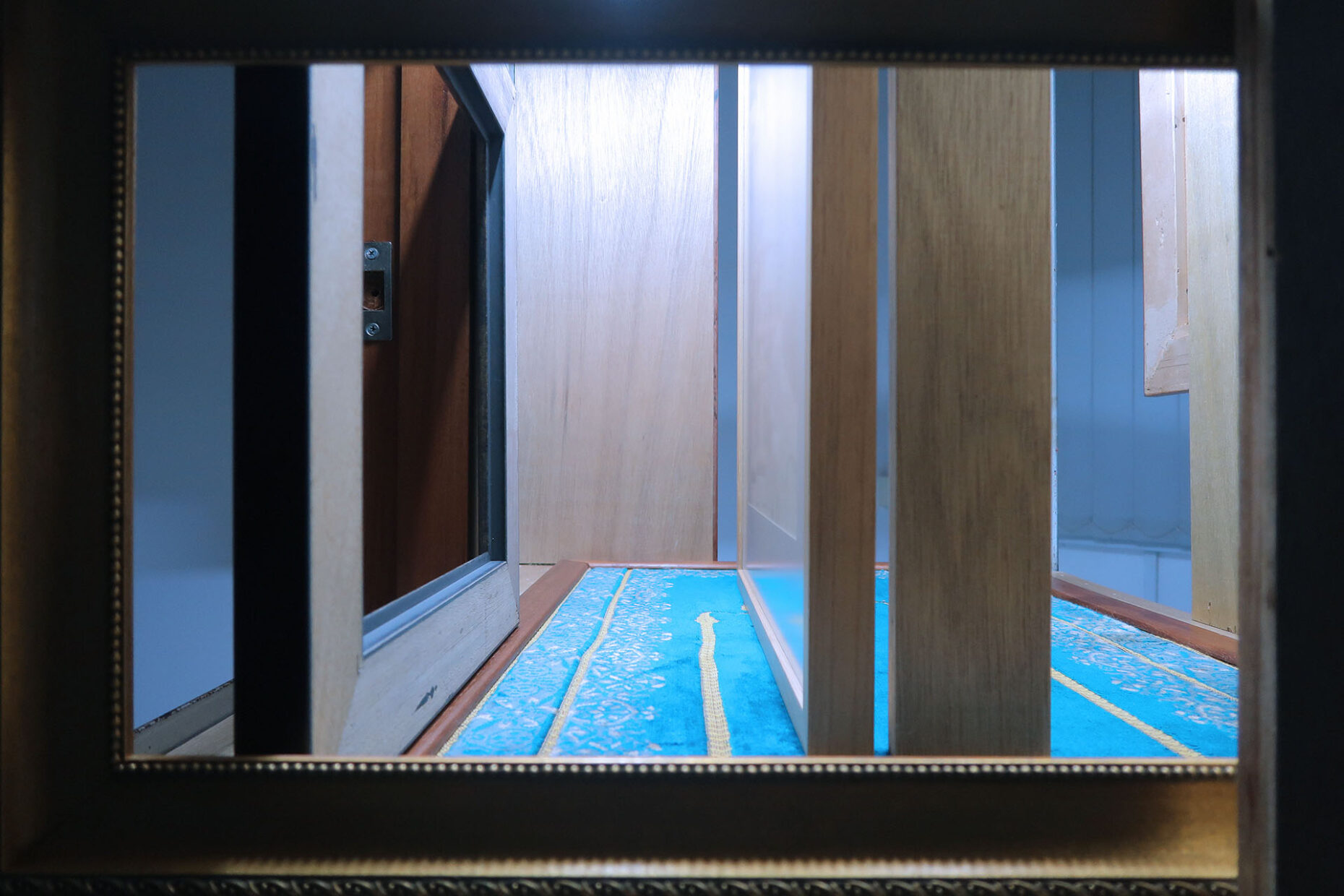

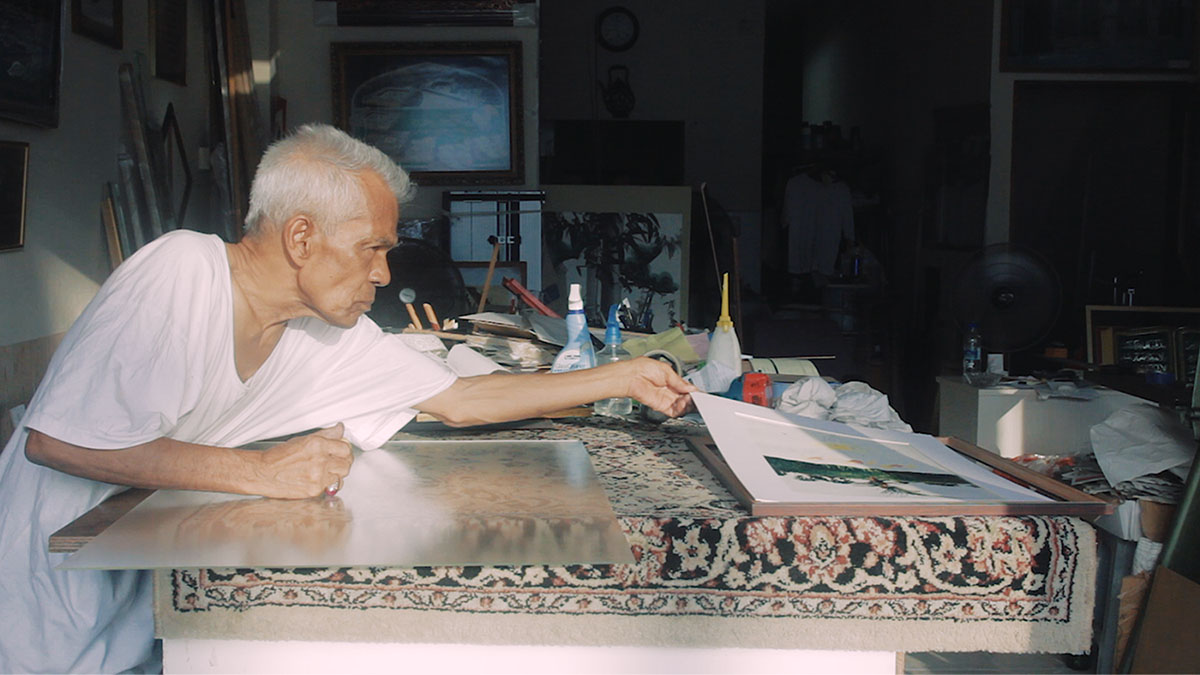

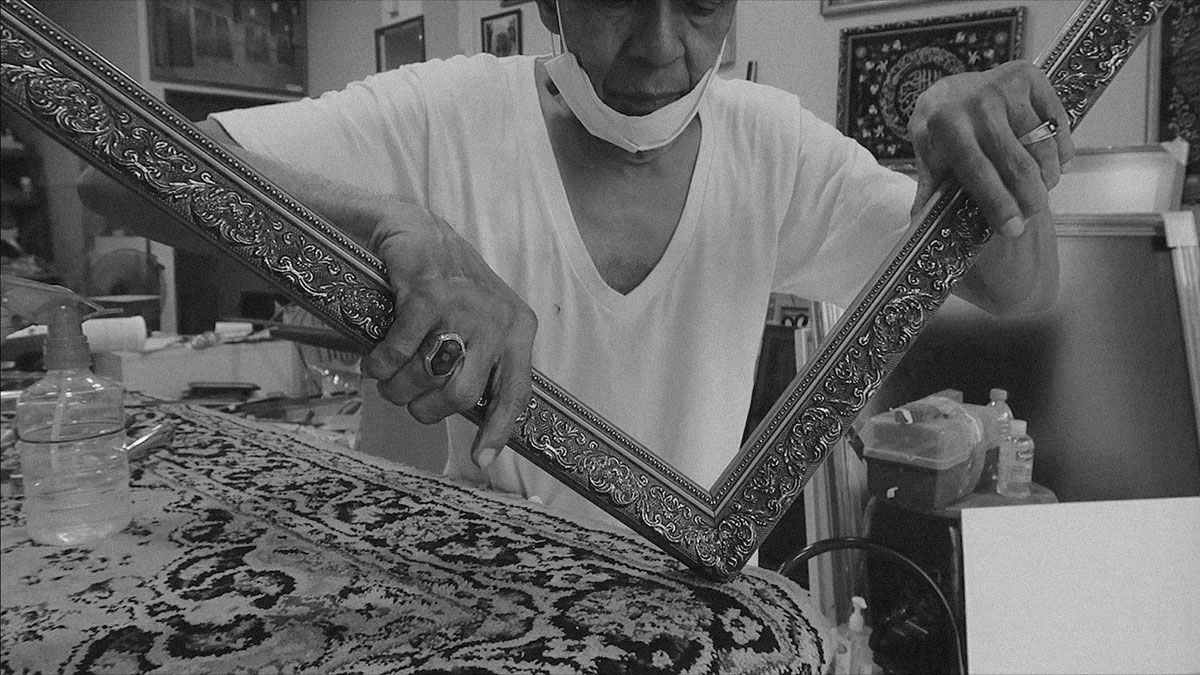

Later, I began learning the craft of frame-making directly from Maricar, and over time, I moved into his workshop to work alongside him. Together, we fabricated around thirty picture frames, each resized and cut from discarded frames left behind by his customers. These recycled frames were then hung on the second floor of the workshop.

What began as a modest collaboration thus grew into a collective process of participation and exchange. We plan to invite his community of friends and customers to contribute artworks to fill the empty frames. The process will culminate in an open house, where the public will be welcomed to view the assembled works. At the close of the showcase, contributors will be invited to return and adopt an artwork as a gift, completing a cycle of making, sharing, and exchange.

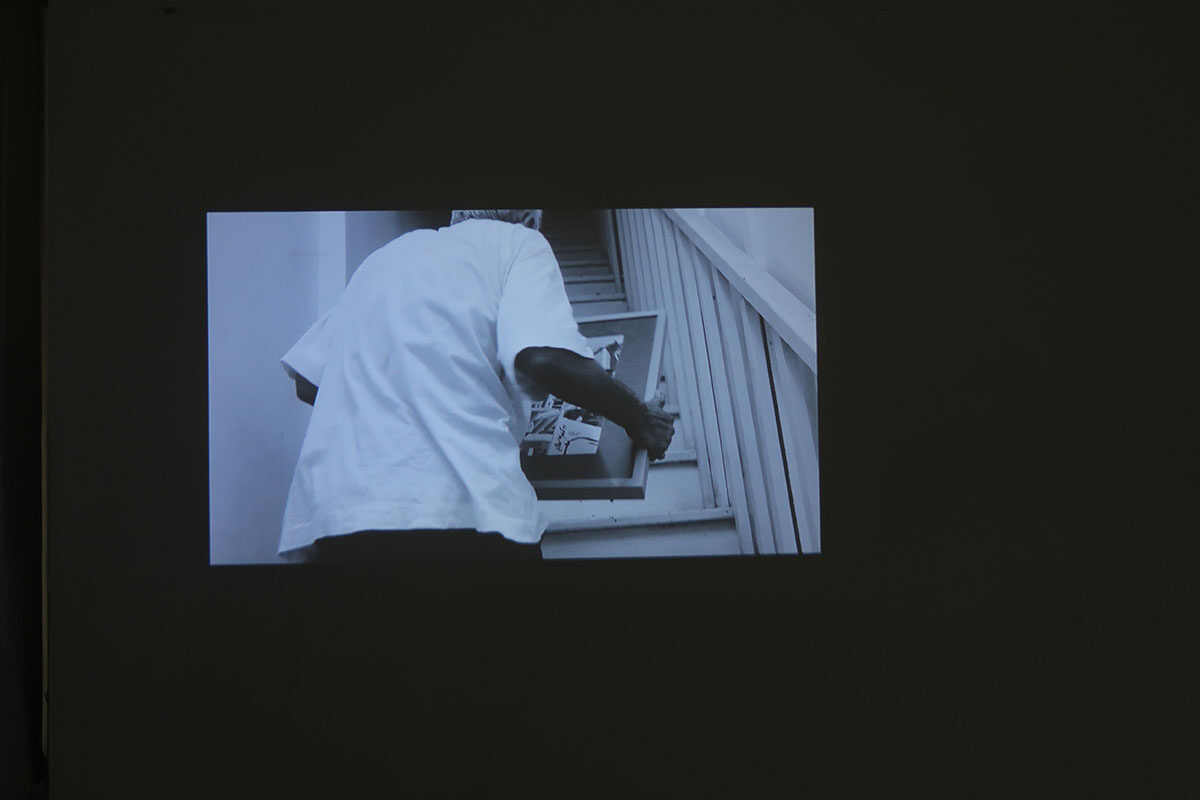

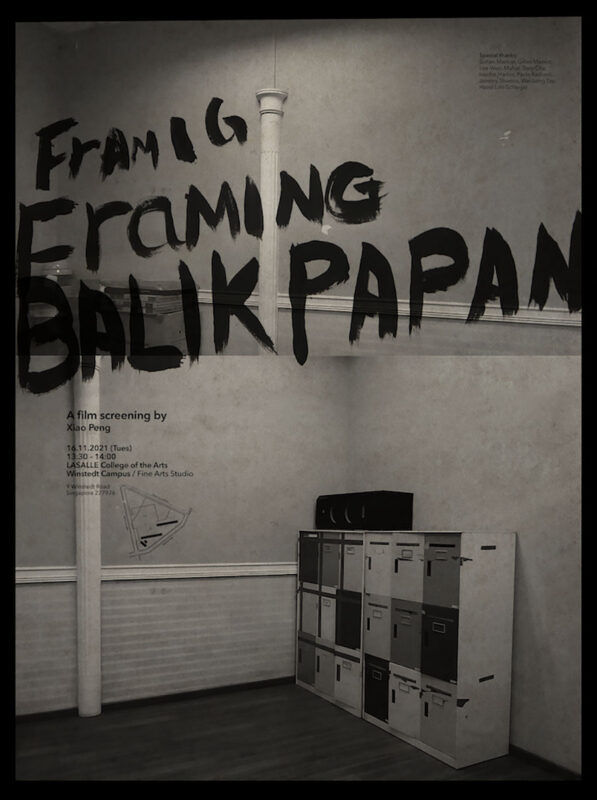

Yet as the project unfolded, circumstances shifted unexpectedly: Maricar and his neighbours were asked to vacate their premises. As the building was cleared, we began working with what remained, juxtaposing debris from the demolition with mixed memorabilia left behind by Maricar during the move, turning the recycled frames into a sculptural installation for a secondary audience. Now in a nomadic phase, Maricar is seeking a new space in Singapore where he can continue his work as a frame maker. (Click HERE for video excerpt.)

Film excerpts: Project Framing Balikpapan (the film), 2022

Thanks to Gilles Massot, Wei Leng Tay, Jeremy Sharma, and Woon Tien Wei.

© 2022–2026